A geoid is a model of Earth’s shape that represents what global mean sea level would look like if extended continuously, even beneath continents. It is not a smooth, simple sphere or ellipsoid; instead, it’s an equipotential surface. This means that at every point on the geoid’s surface, the strength of Earth’s gravity is the same. Because the planet’s mass is not distributed evenly—with features like mountains, ocean trenches, and variations in rock density—this surface of equal gravity potential is complex and undulating.

The geoid serves as the true zero-level reference for orthometric heights, which is what we commonly mean by “elevation above sea level.” Understanding the geoid is crucial because it underpins how we interpret elevations, design infrastructure, model sea-level rise and floods, and monitor Earth processes.

The geoid approximates where global sea level would lie under land, as determined by Earth’s gravity rather than waves or tidal forces. While we can’t place a physical marker on the geoid everywhere, models let us estimate its shape accurately.

Elevations in many applications (flood risk, construction, survey) rely on orthometric heights tied to the geoid; small geoid errors (on the order of cm) can lead to significant misinterpretations in sensitive contexts (e.g. flood mapping, deformation monitoring).

Modern GPS/GNSS measures heights relative to a simple ellipsoid; without a geoid model, those numbers have no direct meaning as “sea-level” elevations. Thus, the geoid bridges raw GNSS data and practical elevation values.

What does it mean to be an “equipotential surface”?¶

The geoid is an equipotential surface, meaning it is a surface where the Earth’s gravitational potential is constant. In simpler terms, if you could walk along the geoid, you would not feel any change in gravity’s pull uphill or downhill. No matter where you go, gravity would always act perpendicular to the surface. Water, for example, will naturally flow from areas of high potential to low potential until it settles on an equipotential surface, like the geoid. This is why it approximates mean sea level: it’s where water “wants” to be when undisturbed.

However, gravity isn’t uniform across the Earth. Local differences in the Earth’s mass distribution, from mountain ranges to dense subsurface rock structures, cause tiny variations in the strength and direction of gravity. These variations pull the equipotential surface into slight undulations rather than following a smooth mathematical ellipsoid.

Imagine suspending a plumb line (a string with a weight) in a flat area. The string points directly toward the center of gravity at that location. Now place the same plumb line next to a massive mountain. The mountain’s mass exerts a gravitational pull of its own, slightly attracting the weight toward it. This means the plumb line no longer points directly toward the Earth’s center but is subtly deflected. This deflection alters what we perceive as “vertical,” which in turn affects how we define “level” surfaces like the geoid.

So, in areas near large mountains, the geoid bulges slightly due to the extra mass, and in areas over ocean trenches or low-density rock, it dips. The result is a globally continuous but irregular surface, one that responds to the Earth’s gravity field rather than its geometric shape alone.

Why is the geoid important?¶

Because GPS provides heights relative to a smooth ellipsoid, ignoring gravity, the geoid is critical for converting those heights into meaningful elevations that relate to sea level. Whether you’re designing a levee, mapping terrain, or predicting flood extents, understanding the true vertical reference (i.e. the geoid) ensures accurate and consistent height measurements worldwide.

How do we measure it?¶

The geoid cannot be measured directly but is inferred by combining:

Satellite gravimetry missions (e.g., GRACE, GOCE) to capture large-scale gravity variations.

Terrestrial and airborne gravity surveys (e.g., NOAA gravity data) for finer regional detail.

Precise GNSS measurements (ellipsoidal heights) at known benchmarks.

Traditional leveling data linking physical benchmarks and tide-gauge observations.

These datasets feed into gravity field models and boundary-value problems to compute geoid undulations (height differences between a reference ellipsoid and the geoid surface). The result is a gridded geoid height model giving, at each location, the amount to subtract from GNSS-measured ellipsoid heights to get orthometric heights.

Ellipsoids and relationship to geoids¶

Reference ellipsoids (e.g., GRS80, WGS84) provide smooth mathematical surfaces for defining latitude/longitude and ellipsoidal heights.

The geoid height at a location is the difference between the ellipsoid and the geoid. Positive values mean the geoid lies above the ellipsoid, negative means below.

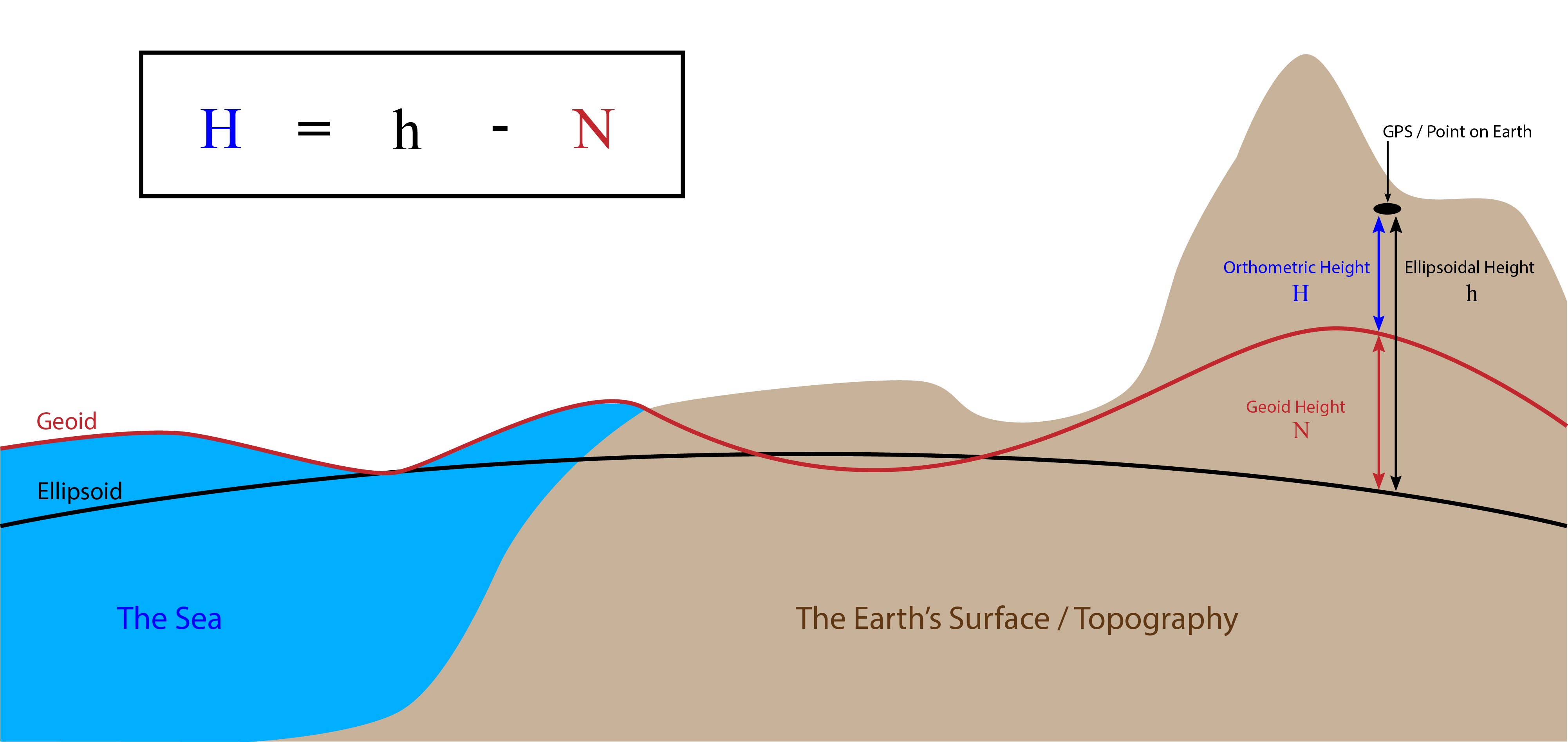

Converting a GNSS ellipsoidal height () to a more meaningful elevation () uses: , where is the geoid height from a model aligned to the same ellipsoid.

Regional geoid models often align the ellipsoid origin in a plate-fixed frame to avoid offsets (e.g., North American plate ellipsoid origin differs by ~2 m from Earth’s center of mass), ensuring consistency in GNSS-derived heights.

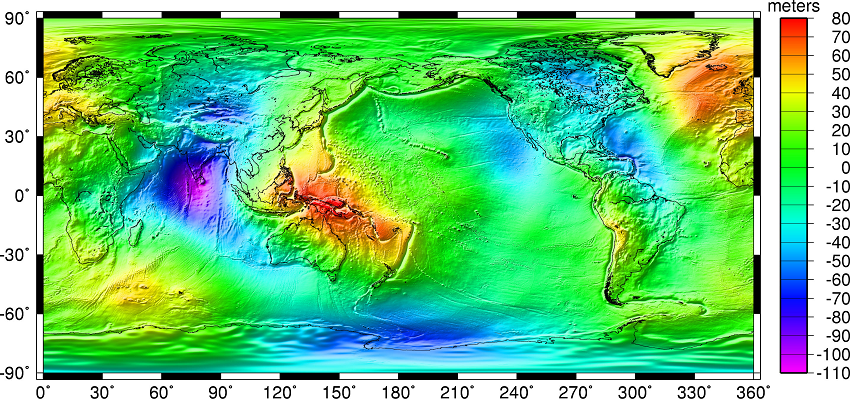

Figure 1:Geoid undulations from the EGM2008 gravity model. Source: NGA. Note that the separation between the lumpy surface of the geoid and the symmetrical reference GRS80 ellipsoid worldwide varies from roughly +85 meters west of Ireland to about -106 meters south of India near Ceylon.

Geoid vs. vertical datums¶

People often mix up the geoid and a vertical datum:

A geoid is a gravity-based reference surface estimated by models; no physical monuments, represented by gridded geoid heights. It provides the correction for converting GNSS ellipsoidal heights into approximations of “sea-level” elevation.

A vertical datum is a defined framework (physical benchmarks, tide-gauge ties, network adjustments) that establishes official elevation values in mapping and engineering. https://

www .intermap .com /blog /understanding -vertical -datums

💡 Tip: An Example in Practice

Imagine a surveyor needs to determine the elevation of a new communications tower on a remote mountain.

Using the Geoid Model: The surveyor uses a high-precision GPS receiver, which measures the tower’s ellipsoidal height (h) relative to the WGS84 ellipsoid. The software on their data collector contains a geoid model (like GEOID18). It looks up the geoid height (N) at that specific latitude and longitude and instantly calculates the orthometric height (H = h - N). This gives an excellent, immediate estimate of the tower’s elevation above mean sea level.

Figure 2:The Difference Between Ellipsoidal, Geoid, and Orthometric Elevations from Virtual Surveyor (software company in Aarschot, Belgium)

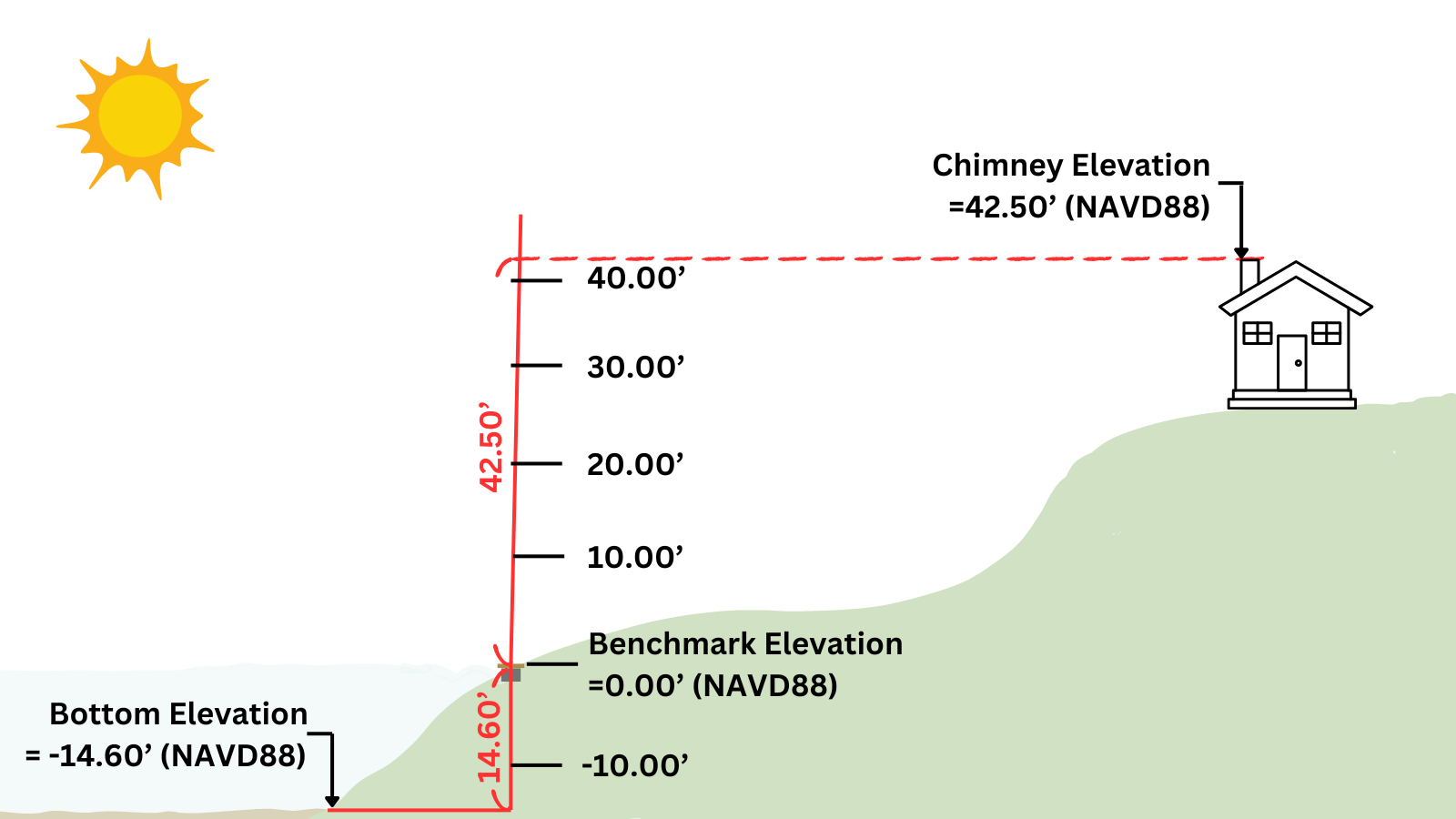

Using the Vertical Datum: Now, imagine the surveyor needs to ensure a new stormwater drain at the base of the tower will correctly flow into the county’s existing drainage system. For this, the geoid-derived height is not sufficient. The surveyor must find a nearby physical benchmark—a metal disk set in concrete with a legally recognized elevation in the official vertical datum (e.g., NAVD88). By performing measurements relative to that benchmark, they ensure their project is perfectly consistent with all other official elevations in the county, guaranteeing the water flows correctly.

Figure 3:This figure illustrates how a vertical datum (NAVD88) provides a physical benchmark with a defined elevation of 0.00', serving as the origin for measuring true orthometric heights. Unlike the geoid model used to estimate elevations from GPS, this real-world reference ensures precise, legally recognized elevations, such as the lakebed at -14.60' and the chimney at +42.50' relative to the benchmark. Image from Washington Surveyor's "What are Vertical Datums? Understanding Elevation References in Surveying".

In this case, the geoid provides a quick, universal height estimate, while the vertical datum provides the authoritative, locally consistent reference required for engineering.

Interaction:

GNSS gives an ellipsoidal height; subtracting geoid height yields an “orthometric” estimate. But for that estimate to match published elevations, it must align with the vertical datum’s realization.

Vertical datums (e.g., NAVD88) originate from leveling networks tied to benchmarks and tide gauges. Geoid models (e.g., GEOID18) are validated to match the datum’s network so GNSS-derived elevations correspond to benchmark elevations.

Upcoming datums (e.g., Modernized NSRS) will rely more on GNSS plus updated geoid models, but the datum still includes conventions (reference frame, epoch) and ties to real-world observations.

Global vs. regional geoid models¶

Global geoid models (e.g., EGM96, EGM2008) offer worldwide coverage from satellite and sparse gravity data; accuracy often limited to decimeters or more.

Regional geoid models refine global models with dense local gravity surveys, GNSS-on-benchmark data, and leveling, achieving centimeter-level accuracy within the region. They align to plate-fixed ellipsoids to avoid tectonic offsets.

In North America, NOAA NGS produces successive models (GEOID03, GEOID09, GEOID12B, GEOID18) integrating new data and improved methods as years progress. These are distributed as raster grids used by GIS and transformation tools (e.g., GDAL/PROJ) https://

geodesy .noaa .gov /GEOID/